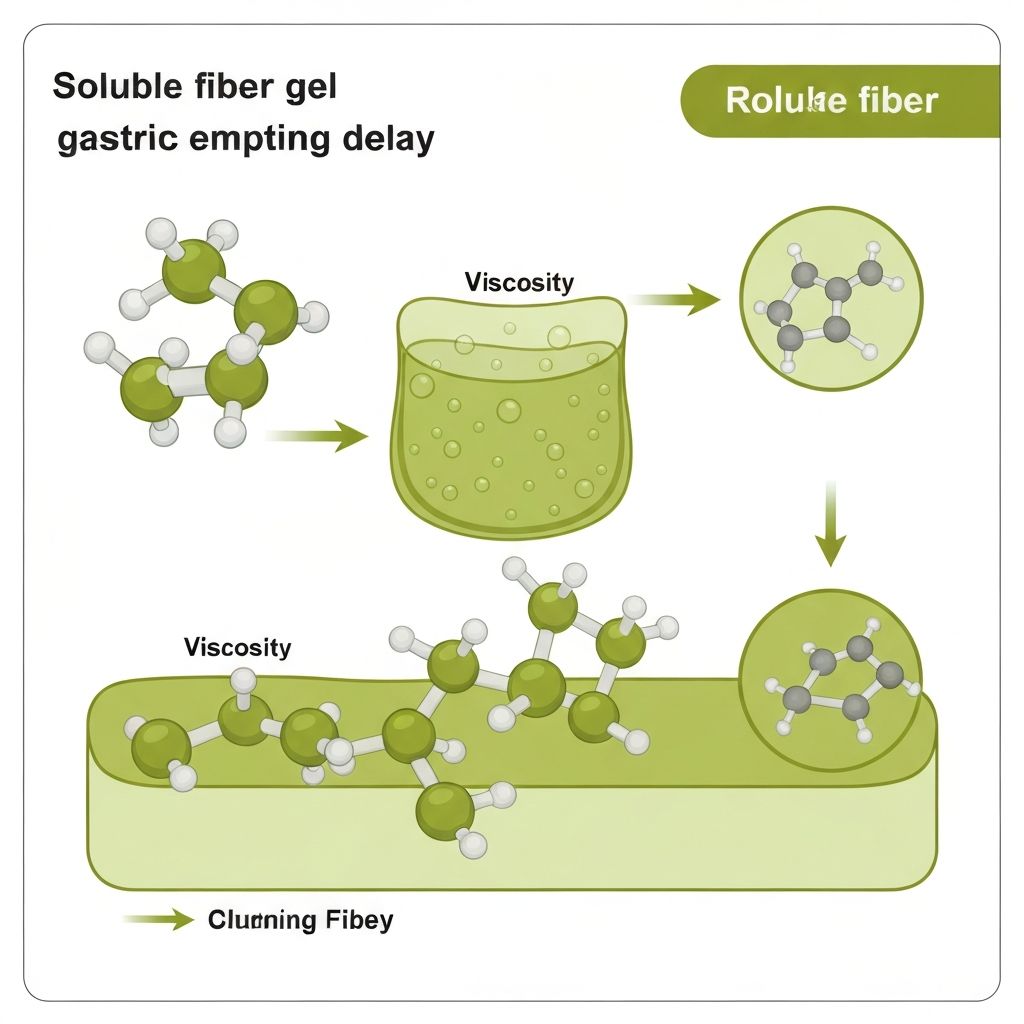

Soluble Fibres and Gastric Emptying Delay

Viscosity and gel-forming properties of soluble fibres and their effects on stomach emptying rate and nutrient delivery.

Viscosity: The Primary Mechanism

Soluble fibres—including beta-glucans, pectin, and inulin—dissolve in aqueous environments to form viscous solutions. This viscosity is not a static property but a concentration- and shear-dependent characteristic that varies during digestion.

In the stomach, fibres form three-dimensional gel networks that:

- Increase gastric contents volume, activating stretch receptors (mechanoreceptors) in the stomach wall

- Reduce the rate of antral contractions, the rhythmic muscular squeezing that propels food into the small intestine

- Enhance interaction between ingested nutrients and gastric mucosal cells, prolonging chemoreceptor signalling

- Modify the rheological properties (flow characteristics) of chyme, reducing the size of particles entering the pyloric sphincter

Gel Formation and Water-Holding Properties

Gel formation occurs through hydrogen bonding and physical entanglement of polymer chains. The extent of gel formation depends on:

| Factor | Effect on Gel Formation |

|---|---|

| Fibre concentration | Higher concentration = greater viscosity and stronger gel structure |

| Molecular weight | Longer polymer chains = increased water-holding capacity and gel strength |

| pH environment | Lower pH (acidic stomach) can reduce gel formation; higher pH (small intestine) may enhance it |

| Ionic strength | Ions in gastric fluid can modify gel crosslinking and viscosity |

| Enzyme activity | Bacterial and digestive enzymes gradually degrade gel structure during transit |

Water-holding capacity—the amount of water retained within the gel network—directly influences gastric distension. Beta-glucans from oats hold approximately 100 mL water per gram, while pectin from fruit holds 30–50 mL per gram.

Neurohormonal Responses to Gastric Distension

Prolonged gastric distension activates multiple signalling pathways:

Vagal Afferent Signalling

Stretch receptors in the stomach wall send signals via the vagus nerve to the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) in the brainstem. This pathway is rapid (seconds to minutes) and does not require nutrient absorption. It contributes to satiety sensation independent of the fibre's chemical composition.

Cholecystokinin (CCK) Secretion

Soluble fibres slow the rate of nutrient entry into the small intestine, prolonging the duration of CCK stimulus. I-cells in the duodenum and jejunum sense amino acids and fatty acids and release CCK. Sustained CCK secretion (rather than a single pulse) produces stronger satiety effects and further slows gastric emptying through negative feedback.

Gastric Inhibitory Peptide (GIP)

GIP secretion from K-cells in the proximal small intestine is stimulated by glucose and fatty acids. Soluble fibres delay this stimulus, which modulates the insulin secretion and satiety responses.

Practical Evidence from Gastric Emptying Studies

Scintigraphic and ultrasound studies have quantified gastric emptying delays produced by soluble fibres:

- Beta-glucan (5 g): 20–30% reduction in 30-minute gastric emptying rate compared to control meal

- Psyllium husk (10 g): 25–40% delay in half-emptying time (median duration for half of meal to leave stomach)

- Pectin (5 g): 15–25% reduction; effects are more modest and shorter-lived (recovered within 60 minutes)

- Guar gum (5 g): Up to 50% delay in gastric emptying; strong effects on both liquid and solid meal components

These delays translate to sustained nutrient delivery and prolonged satiety hormone signalling. Studies using visual analogue scales (VAS) show corresponding reductions in hunger ratings 60–120 minutes postprandially, with some studies reporting sustained effects up to 3 hours.

Factors Affecting Efficacy

The satiety effect of soluble fibres is not uniform across all individuals or conditions:

Fibre Dose

Satiety effects exhibit dose-dependency up to approximately 10–15 g per meal. Higher doses do not necessarily produce proportionally stronger effects and may cause gastrointestinal distress.

Meal Composition

Fat and protein content modulates fibre efficacy. High-fat meals already slow gastric emptying; co-ingestion of soluble fibres with high-fat meals produces less pronounced additional delays (marginal gains). Protein-rich meals benefit more from fibre addition.

Fibre Particle Size and Preparation

Particle size affects hydration rate and gel formation kinetics. Finely ground beta-glucan reaches peak viscosity faster than coarse particles. Preparation method (whole grain vs. isolated fibre extract) influences the temporal profile of gel formation.

Individual Variation

Baseline gastric acid secretion, stomach volume, muscle tone, and vagal sensitivity vary between individuals, accounting for 15–25% variance in satiety responses to soluble fibres. Individuals with rapid gastric emptying rates (risk factor for postprandial hyperglycaemia) may benefit more from viscous fibre supplementation.

Mechanisms Beyond Gastric Distension

Soluble fibres produce satiety effects through multiple independent pathways:

Delayed Nutrient Absorption

By prolonging transit through the small intestine, viscous fibres delay the rate of glucose and fat absorption. This maintains postprandial blood glucose stability and sustained nutrient sensor activation (GPCRs on small intestinal epithelial cells), extending satiety signalling duration.

Increased Ileal Brake Activation

The ileal brake is a feedback mechanism whereby lipid delivery to the terminal ileum triggers GLP-1, PYY, and CCK release. Soluble fibres promote nutrient delivery to the ileum (rather than rapid small intestinal absorption), extending and amplifying ileal brake signalling.

Osmotic Effects

Some soluble fibres (e.g., inulin, oligofructose) exert osmotic effects, drawing water into the intestinal lumen. This increases chyme volume and distends the bowel, activating stretch receptors throughout the small intestine and colon.

Limitations and Adaptation

Prolonged soluble fibre consumption may result in adaptation:

- Gastric smooth muscle may habituate to sustained distension over 2–4 weeks, reducing satiety sensation

- Gel viscosity may decrease with time as digestive enzymes gradually degrade fibre polymers

- Individual microbiota changes can alter fermentation rates and SCFA profiles, shifting satiety mechanisms

- Enzyme induction in the small intestine may increase nutrient absorption rate, counteracting the initial delay

Key Takeaways

Soluble fibre satiety effects are mediated primarily by viscosity-induced gastric distension and delayed nutrient delivery, with secondary contributions from prolonged gut hormone secretion. The magnitude of effect depends on dose, fibre type, meal composition, and individual physiological variation. Understanding these mechanisms provides context for observing variable satiety responses across individuals and meal types.